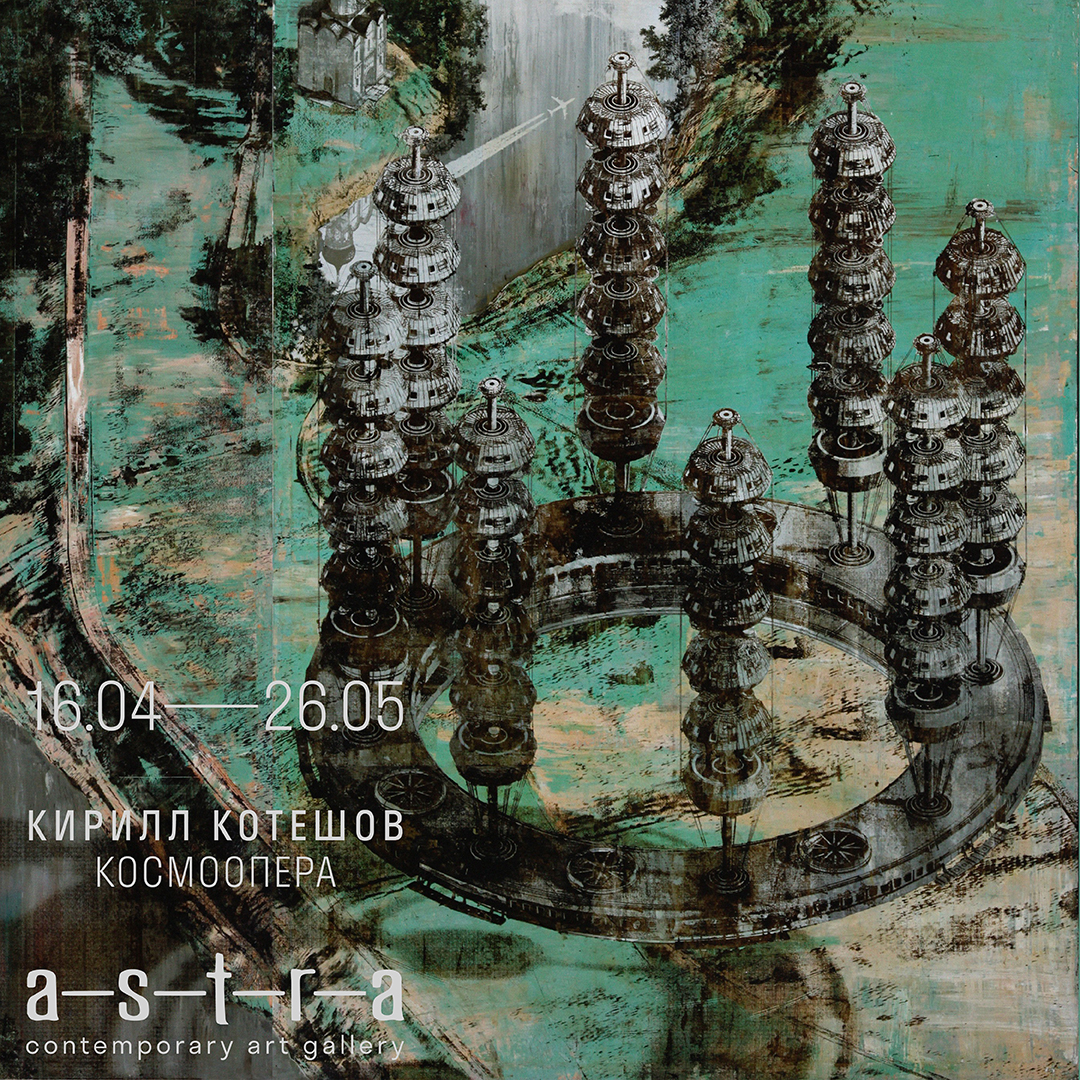

solo show Kirill Koteshov

COSMOOPERA

Winzavod Central Exhibition Centre

4th Syromyatnichesky Lane, 1/8, p. 9

16.04 — 26.05.24

‘When historical time twists into the apocalyptic spiral of the heavenly vault folded by angels, the epoch of timelessness arrives. The progressive ideas of modernism collapse. Postmodernist irony does not save. ‘Other places’, utopias, heterotopias, atopias help to live. Kirill Koteshov organises his ‘other places’, calling on the imaginary architecture of the Russian avant-garde as an ally.

Imaginary architecture as a genre emerged during the Renaissance and was first understood as sublime fantasies of the ideal city. In the Mannerist era, imaginary architecture led to the realm of melancholy and represented punished pride and human vanity (Tower of Babel). In Giovanni Battista Piranesi's suite of etchings from the middle of the 18th century, ‘Carceri’ (‘Prisons’), the torture architecture of dungeons bursts into the fourth dimension and builds itself. Its structures - bridges, wheels, levers - do not obey the logic of human presence. With their aggressive outward attack, they enslave people. They make them prisoners. In the Soviet avant-garde of the 1920s, architecture is put at the service of people, who are obliged to acquire the power of giants. The utopia of progress promises cyclopean buildings created according to the laws of intelligent geometry (Vladimir Tatlin's Tower of the III International). The visionary projects of Ivan Leonidov and Georgy Krutikov make us believe in flying cities, in which the ideas of the Renaissance (Tomaso Campanella) about an ideal communist society illuminated by the rays of the eternal sun take on a new life.

Kirill Koteshov's virtuoso graphic technique puts him on a par with the heirs of all the imaginary architecture projects described above. In his series, the Master seems to pass this architecture through the filter of the so-called ‘paper design’ of the late Soviet era of the 1980s-1990s. At that time, the progressive utopia of modernism gave way to a postmodernist game of quotation. Alexander Brodsky, Ilya Utkin, and Yuri Avvakumov began to create largely melancholic spaces in which avant-garde projects turned into fragile capriccio of graphic fantasies or ruinous sites of vanished civilisations.

The paper architecture of the USSR is very malleable in order to translate the arrows of the former utopia with its promise of universal happiness, or the ancient anti-utopia with its carnivorous dungeons, into the world of other places, ‘heterotopias’, in which reality becomes virtual. This ‘other reality’ with the stopped course of time is very sensitively directed in his silkscreens by Kirill Koteshov. Using a complex technique that combines oil with bitumen, Koteshov creates an ‘alternative present’. This ‘alternative present’ inherits, on the one hand, the fantasy genre and cyberworlds, on the other hand, ancient illusions with eternal sunshine and hallucinogenic landscapes. Landscapes were given to us by Baroque opera culture, the forerunner of virtual locations of computer games. In fact, the developers of games such as Assasin's Creed hire a whole staff of scholars of old culture to make all locations of antiquity phenomenally detailed and attractive.

In Koteshov's works, Georgiy Krutikov's chandelier houses floating in the airless space are drawn in such a way that you can feel every element of the cladding with your eye. These forms are inscribed in a radiant, moving, fluid landscape. In it you unexpectedly meet a temple of Vladimir-Suzdal architecture. And Tatlin's tower is built by Koteshov as if from block panels, the same ones that pioneered the architecture of the Thaw in the second half of the 1960s.

This hybrid assemblage of ‘other places’ helps to understand another important problem for the artist: globalisation and loss of identity in the world of ‘rolled-up time’. The Cosmo-opera presented in a—s—t—r—a gallery is directed by the artist as if it were a collage of various mythological and real-life stories. It captivates both as a fantastic blockbuster film and as an ancient epic about cultural archetypes, and as a meta-irony on the theme of ruinous consciousness and faceted perception of the world by a man of the XXI century’.

text by Sergey Khachaturov